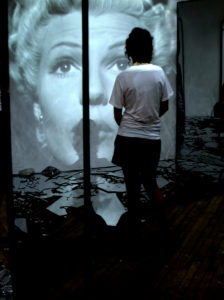

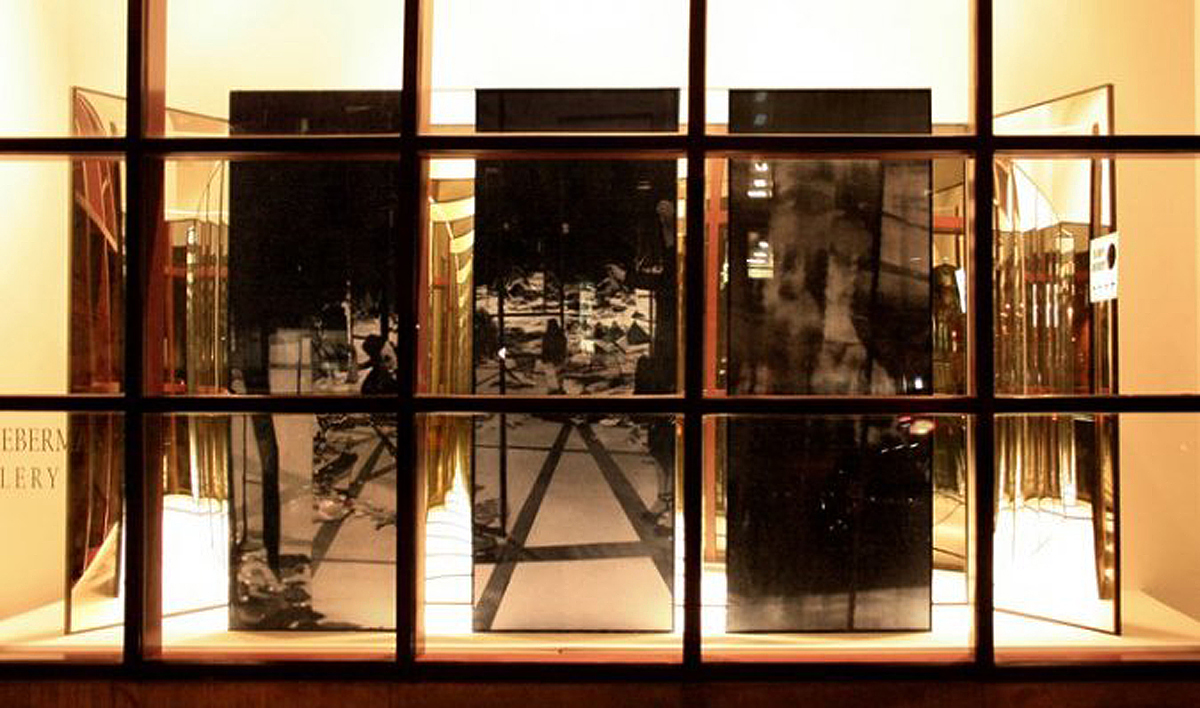

This installation references the ambiguity of space and time as it is depicted in the final dramatic shootout in a hall of mirrors in Orson Welles’s 1947 film, The Lady From Shanghai. The installation consists of a network of paintings, mirrored surfaces, and empty black metal frames that make direct architectural reference to a traditional mirror maze and pulls the viewer into a dislocating, perceptive experience. Unlike in the cinema house, where the images move and the viewer remains still, here the viewer moves through the space, and enters an illusory representation of cinematic space and time. Slowly walking around the frames, the viewer realizes that certain parts of the image are repeated in separate paintings, and that each painted image is only one layer in a complex fragmented depiction. Three cut out and painted, life-size figures that belong to the scene literally exist outside the paintings, but are also able to melt back into them. So the viewer’s sense of spatial clarity in the image continually falls in and out of place. Once the viewer walks through the mirror maze section they enter into a video space surrounded by plexi mirror on the walls and hundreds of fragments on the ground. Looking back towards the front of the gallery, one sees that all the backs of the paintings, including the backsides of the figures, are mirrors. The viewer has entered a separate illusory space from the painted illusion they experienced while walking through the installation. The projected video Last Breath on the Mirror slows down and speeds up the abstract beauty of the shattering mirrors within the scene, synchronized to a variety of tempos in a soundtrack created in collaboration with a DJ, through remixing and resampling dialogue, music, and sounds from the film, but also includes fragments from Hank Williams’s ballad, The Angel of Death.

Installation Views are from Jade Art Gallery, Bergamo, Italy, curated by Sara Mazzocchi, film curator, Galeria, d’Arte Moderne e Contemporanea, Bergamo, Italy

Marcelino Stuhmer, Get Ready to Shoot Yourself, Exhibition Catalogue

Catalogue Essay, You Need More then Luck in Shanghai, by Sara Mazzocchi

VOX VIII, Vox Populi Gallery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, juried by Ruba Katrib, Sculpture Center, NY

VOX VIII, The Material Unreal, ArtBlog, By Libby and Roberta, 7/22/2012

Window Installation View from Cinematic Bodies at Zolla Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, IL, Curated by Jamie Adams

The Angel of Death was coincidentally written in late 1948 and first recorded in early 1949, precisely the time that The Lady from Shanghai was released in American theaters. More than fifty years after his tragic death at age of 29, Hank Williams ranks among the most powerfully iconic figures in American music. Iconic to the point that man and myth are inextricably linked. He set the agenda for contemporary country, folk, and popular songcraft and sang his songs with such believability that we feel invited into the authenticity of his dark and brooding world. My choice to appropriate The Angel of Death for use in the installation video, is a subtle reference to the well-known legend that Rita Hayworth’s famous pinup photo from Life Magazine, that sold 5 million copies during WWII, which was painted on the sides of hundreds of war planes, ships, and just about everywhere servicemen went, was most notoriously painted on the first atomic bomb tested by the United States in 1946 on the island of Bikini Atoll. The bomb was nicknamed Gilda after the steamy role she played that same year, referencing her “Bombshell” sex symbol status.

The real content under the surface of this project focuses on the illusory identity of Rita Hayworth,. She was born Margarita Carmen Cansino in New York City on Oct. 17, 19l8. Her father, Eduardo Cansino, was a Spanish-born dancer and her mother, the former Volga Haworth, had been a broadway dancer and Ziegfeld Follies showgirl. After a brief stint dancing with her father in Tijuana, she was discovered by Fox studios and made 10 movies under the name Rita Cansino. In 1937 she met and married Edward Judson a shrewd businessman 22 years older than her. Under his influence Rita had her eyebrows and hairline painfully altered through constant electrolysis, dramatically, culturally, and ethnically transforming her from a black-haired Latina into an auburn-haired white American bombshell. As her manager, Mr. Judson also changed his wife’s professional name, choosing her mother’s maiden name of Hayworth to further Anglicize her identity. Beginning in 1941, Miss Hayworth rapidly developed into one of Hollywood’s most glamorous stars, earning her the title ”The Great American Love Goddess.” Many have written about Hayworth’s loss of cultural and ethnic identity, and then her loss of subjectivity due to constant commodification, which is precisely the reason the closeups of Rita’s face exist within the film, they were ordered by the studios to cash in on her seductive image. Rita Hayworth’s Elsa Bannister, is the mysterious black hole at the center of the Lady from Shanghai. When Welles’s Michael O’Hara met her, against all reason he couldn’t help but get sucked right into her labyrinthine murder plot. So O’Hara’s story is in fact a tale of survival, and in his final words he makes it clear that surviving is forgetting. He seems more intent on forgetting Elsa’s face than her persona; it’s her image, which has been burned into his psyche, he walks out because he cannot look at her without immediately falling in love with her image once again. This is mythology, not misogyny, as some critics have argued. Yet the tragic irony of Miss Hayworth’s personal life, was the suffering from a very real case of Alzheimer’s disease from the mid to late 1970’s until her death in 1987. At the end of her life Rita Hayworth became completely dependent upon her daughter Princess Yasmin Kahn. Earlier in life she had playfully and sarcastically commented, “Men fell in love with ‘Gilda,’ but they woke up with me.” Now she would not recognize her own famous face in the mirror, regardless of any of her real or fictional personas. She had been reduced to becoming less than an image, she was a recurring “found image” that was immediately forgotten. Placing the incredibly famous pinup and “American love goddess” Rita Hayworth at the center of the mirror maze, was not just about the indiscernability of the real and the virtual within the film, but it is poses the question of whether the so called “real” Rita Hayworth, was herself an illusion, and only alive as an image. Welles’s ambitious mirror maze becomes incredibly important within the history of representation, including painting, photography, video, and installation art, because it does indeed comment on, and further predict the increasing commodification of images, beauty, and the illusion of the immortal celebrity, that Andy Warhol was to explore in more depth 20 years later.